Whether weddings, national parades or religious festivals, rituals present a puzzle. We stress their importance, reflecting on these services as some of life’s most cherished moments. And yet, when prompted, most of us can’t explain why we perform them. What explains their persistence, and this apparent contradiction?

In his new book Ritual: How Seemingly Senseless Acts Make Life Worth Living, trailblazing anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas takes us on an electrifying tour of the world’s most exotic and extreme rituals. By fusing the latest breakthroughs in science and technology, Xygalatas presents a powerful new perspective on our most sacred ceremonies.

Ancient traditions

A native of Greece, rituals have fascinated Xygalatas since his early childhood. Flicking through his first copy of the National Geographic and learning about exotic cultures in faraway places sparked his curiosity, planting the seeds of his career in anthropology.

Ironically, Xygalatas started out as a ritual sceptic. “To me, the human obsession with ceremony seemed puzzling”, Xygalatas writes. “Why do so many strange traditions persist in the modern age of science, technology and secularisation?”

Xygalatas’s worldview was shaken when his father took him to his first football game. “For most of the game my father kept trying to lift me up so that I could watch the action. But that didn’t matter much to me. The most interesting part was what was happening in the terraces”. Forming a sea of black and white shirts, forty thousand football fans created a spectacle Dimitris would never forget. “As soon as the referee blew the first whistle, it was as though a jolt of electricity had run through the stadium . . . It was as though the crowd had become a single entity with a life of its own.”

According to Xygalatas, sports events like this mirror some of our most primitive ceremonies. “There is something about high-arousal rituals that seems to thrill groups of individuals and transform them into something greater than the sum of their parts.”

Even as the Western world loses its religion, Xygalatas argues that rituals remain rampant. “From knocking on word to uttering prayers, and from new year celebrations to presidential inaugurations, ritual permeates every important aspect of our private and public lives.”

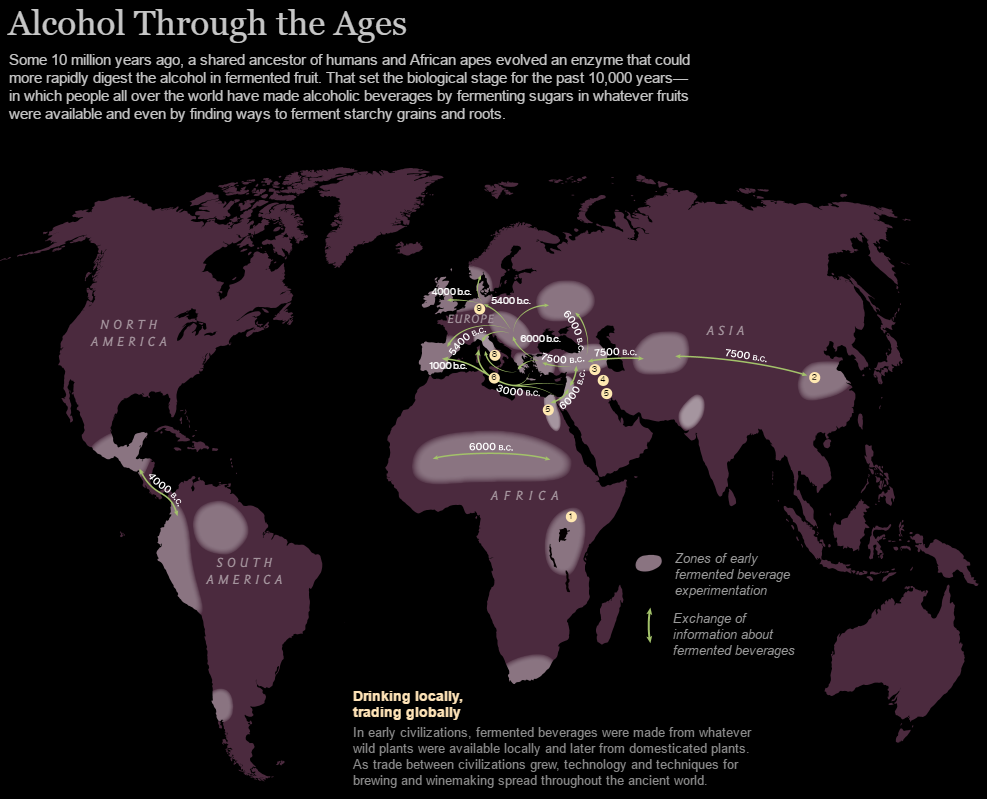

Evidently, the human desire to congregate is ancient. From prehistoric hunter-gatherers to the urbanites of the 21st century, people across cultures and throughout history have felt compelled to form large crowds and participate in communal ceremonies.

The oldest known ritual is the funeral, where archaeologists have unearthed evidence of burials taking place over a hundred thousand years ago. However, humans do not hold a monopoly on rituals. Whether it’s the ritualised greetings of chimpanzees, frisky flamingos engaging in elaborate courtship rituals, or elephants trekking vast distances to pay respect to their dead, rituals have been spotted across the animal kingdom. That said, Xygalatas stresses the prevalence and extent of our ritualistic practices is uniquely human.

My findings, as well as convergent discoveries from a variety of scientific disciplines, reveal that ritual is rooted deep in our evolutionary history. In fact, it is as ancient as our species itself – and for good reason.

One camp of scientists argue that the gravitational pull of rituals is an evolutionary accident, and that our ritualistic behaviour is the result of misfiring mental systems that detect danger. Although the ‘mental glitch hypothesis’ should be taken seriously, Xygalatas argues the weight of evidence is stacked against it. “Evolution is not wasteful”, asserts Xygalatas. “Behaviours that are impractical or maladaptive do not tend to stick around forever.”

Social glue

So, what are the functions of rituals then? In essence, Xygalatas argues that rituals are cultural gadgets that help solve a raft of recurring challenges we modern humans face. These challenges include: finding a romantic partner, coping with the pain of losing a loved one, and instilling a sense of order in a chaotic world. Perhaps most importantly, rituals help solve the central challenge of getting large groups of fiercely tribal primates to cooperate.

Anthropologists have long explored the functions of traditions, amassing rich descriptions of the world’s most exotic rituals. Despite the groundwork they laid, Xygalatas points out that anthropologists rarely put their theories to the test.

Through his ingenious use of biometrics, Xygalatas reveals that rituals can now be detected in the human body. That is, by measuring how hard people’s hearts are pumping, and other aspects of their physiology.

Xygalatas first experimented with these gadgets in the Spanish village of San Pedro, Manrique. Held on the summer solstice, the ‘festival of San Juan’ floods their small village with visitors, who catch a glimpse of the locals walking bare foot across burning hot coal. Xygalatas got the idea when heard people repeatedly say that when they go out onto the stadium, ‘all three thousand people feel like one’. To Xygalatas, this sounded like what the eminent sociologist Emile Durkheim called ‘collective effervescence’— a pulse of energy that runs through a large crowd and transforms them into a cohesive unit. Perhaps these biometric sensors can capture this sense of oneness?

Clearly, this firewalking ritual evokes strong emotions—and the intensity of these emotions is felt by everyone. Xygalatas and his colleagues’ research revealed an extraordinary level of synchrony among people’s heart rates, both amongst the firewalkers and spectators.

Ultimately, extreme rituals like the San Juan firewalk trigger a flood of stress and emotions, which in turn binds people together. “Each individual’s experience is affected and amplified by those of others, like a thousand streams of water merging to form a river that is faster and more powerful than any single stream could ever be.”

The dark side of rituals

Rituals are a source of magic, and like all potions, they can be used for good or ill.

Take degrading initiation rituals, also known as ‘hazing’ in the United States. As the crushing weight of pain and humiliation can only really be appreciated by those who have experienced such an ordeal, hazees quickly become comrades. This helps explain why societies at war perform much more brutal initiations, as these rituals instil cohesion at a time when solidarity is absolutely essential. However, Xygalatas suggests if we take these rituals out of context and perform them for no good reason (say, performed at a frat party for shits and giggles), they can be extremely harmful.

That said, there are a range of rituals that seem terrible on the surface, where Xygalatas and his research team have scratched to reveal these rituals’ hidden benefits. Exhibit A: the Thaipusam festival. Performed by millions of Tamil Hindus every year, the Thaipusam is one of the world’s oldest religious festival. The most extreme aspect of it is the Kavadi Attam, where devotees are repeatedly punctured with needles whilst carrying heavy shrines in a long procession to their holy temple (are you tempted?).

If you expect undergoing such hell would trash your health, you’re mistaken. Whilst the pilgrim’s wounds healed quickly, Xygalatas and his colleagues discovered their mental health was substantially improved through suffering this torment— where those who suffered the most experienced the greatest psychological benefits.

A sceptic would argue that there are other activities that offer similar benefits and carry far less risk. For example, intense exercise has been shown to be as effective as antidepressants in treating major depression. However, Xygalatas notes the conundrum of getting someone who’s suffering depression to summon the strength to go for a run. “Cultural rituals may help circumvent this problem by exerting external pressure to participate.”

Ritual feasts

Whilst exploring some of the world’s most exotic and extreme rituals, Xygalatas also reflects the more mundane moments in our lives, including the artificial landscape of the modern workplace.

There are sound ethical and legal reasons why you don’t want to subject your teams to extreme rituals (HR would not be pleased to hear of new hires having needles stuck in their backs). And whilst drinking is an easy way to alleviate anxiety in awkward social situations, the appropriateness of alcohol in work settings is increasingly being called into question. However, there are alternatives that are both suitable and effective.

Having lived in Denmark, Xygalatas documents what he deems peculiarities of Danish working practices. The Danes apparently work less than virtually all other nations in the world. Whilst this can help us understand why Danes are so happy, they certainly aren’t slackers. To the contrary, Danes are also amongst the most productive workers in the world. How on Earth is this possible?

Whilst numerous factors are probably involved, Xygalatas suspects Danish workplace rituals can explain their striking successes. “While at first glance the numerous rituals of the Danish workplace may have seemed odd or wasteful, as soon as I embraced them it became clear to me that they contributed something vital to the efficient, productive and enjoyable work environment.”

Although less time crunching spreadsheets can be perceived as wasting company resources, the Nordics appreciate the social benefits of team activities and communal feasts, and that these benefits more than outweigh the costs. “Eating together is an intimate act, usually reserved for close relatives and friends. Sharing food therefore symbolises community and helps strengthen bonds among colleagues”.

Focusing further afield than efficiency, Xygalatas suggests that communal feasts and team activities effectively harness the power of rituals, strengthening social bonds whilst also boosting morale. “What is more, work group rituals make work-related tasks feel more meaningful, which makes for a happier as well as more productive workforce.”

Of course, it’s not as easy to forge strong bonds amongst corporate workers, as does, say, devotees enduring backbreaking toil in a long procession to their holy temple. However, sprinkling the modern workplace with rituals can help the ordinary feel a little bit more meaningful and special.

Written by Max Beilby for Darwinian Business.

Ritual: How Seemingly Senseless Acts Make Life Worth Living is published by Profile Books. Click here to buy a copy.