An evolutionary perspective provides a powerful way of thinking about employees’ health.

What I’ve outlined below is Zhen Zhang and Michael Zyphur’s chapter on employee health and physiological functioning, in Stephen Colarelli and Richard Arvey’s volume The Biological Foundations of Organizational Behavior. The chapter provides a wealth of information regarding employee health and physiology, and I’ll focus mainly on the practical applications rather than its theoretical contributions.

Zhang and Zyphur’s thesis is essentially this: modern working environments presents novel stressors and social difficulties for which humans have not yet adapted to. The authors propose that these challenges present an evolutionary mismatch, and suggest ways of aligning modern working conditions with that of our ancestral past.

Of course, the forces of technology have been unleashed and there’s no going back to the stone age, and nor would we want to. However, aspects of our humanity are arguably being ignored in modern organisations, and the authors propose some reasonable actions which can help improve employees’ health and physiological functioning.

Evolutionary Psychology and Employees in Modern Organisations

The authors argue that the majority of human psychological mechanisms are adaptations to Pleistocene environments. A classic example of our ancient psychological quirks outlined is that most people are more fearful of seeing snakes and spiders than having a loaded gun pointed at them, despite the fact that guns kill significantly more humans annually than snakes and spiders combined. This is because snakes and spiders were a constant threat to our ancestors during the Pleistocene, whereas guns are a recent invention and thus a novel threat.

Zhang and Zyphur argue that the mismatch between the environments in which we evolved and those in which we find ourselves in create ‘substantial difficulties’ at work. Specified are many aspects of the modern working environment that were absent in our ancestral past, including: a stricter organisational hierarchy, larger workloads, relative lack of social support, reduced physical activity, lack of sunshine in office and factory settings, sleep deprivation due to shift work, and work-to-family conflicts.

Evolutionary psychological research suggests that we humans evolved in the context of small tightly knit groups, with strong ties and support mechanisms- as do indigenous cultures across the world. The authors note that employees often work in small groups like our ancestors did. However, large modern organisations are populated by people who do not know each other personally, which presents challenges for cooperation and collaboration in light of our evolutionary drives to wrangle over status.

Social Status

Although rising income inequality makes pronounced status differentials appear largely inevitable, one must appreciate that we humans are primarily an egalitarian primate. The authors cite anthropologist Christopher Boehm’s book The Hierarchy in the Forest, which documents hunter-gathers having largely flat structures in their social lives, and that their levels of egalitarianism are far greater than that of modern organisations. I would throw in here that it is the process of cultural group selection which has enabled greater status differentials within and between groups.

The authors argue that the mismatch between small egalitarian groups and that of large hierarchical organisations creates status hierarchies that are difficult to comprehend, and are a source of chronic stress. Further, Zhang and Zyphur argue that these large differences in status induce desires for success that lead people to “place unreasonable demands on their time and mental energy in order to ‘get ahead’, sacrificing their mental and physiological health in the name of social status and material wealth.” (p. 141).

Surprisingly, the authors did not cite the ‘Whitehall studies’. The Whitehall studies was a series of longitudinal research which commenced in the 1960s, that investigated the health of over 17,530 male UK civil servants. Contrary to the researchers’ expectations, the studies demonstrated that the civil servants with the highest status jobs actually were the least stressed, and subsequently the healthiest employees.

Men in the lowest grade were 3.6 times more likely to die from heart disease than the highest grade. However, the lower grades were associated with various risk factors, such as obesity, smoking, and decreased leisure time. Statistically holding these risk factors constant, the lowest grade were still twice as likely to die from heart disease than the highest grade.

20 years later, the ‘Whitehall studies II’ corroborated these findings. The researchers concluded the Whitehall Studies II stating; “Healthy behaviours should be encouraged across the whole of society; more attention should be paid to the social environments, job design, and the consequences of income inequality.”

Workload

Another big development is the sheer volume of work that is characteristic of modern working life.

Anthropologists estimate that in earlier periods of human evolution, people most likely worked up to 8 hours per week. However we now work between 40-80 per week, which is an order of magnitude greater. In order to survive in industrial society, we have to work much harder than our great ancestors did.

The authors state that this rapid shift in workload has resulted in our physiological systems failing to adapt to the new environment, resulting in chronic stress, and a deterioration of social relationships (which buffer the adverse impacts of stress). Zhang and Zyphur state that the increased workload can help explain the prevalence of stress-related physiological maladies we are experiencing today, such as high blood pressure and heart disease.

From an evolutionary perspective, the authors suggest that milder forms of physiological responses can be considered as evolved defence mechanisms that alert people and help them cope with threats and adversities. These responses prompt adaptive behaviours when they are within normal ranges. However, sharp changes in the work environment can lead to excessive stress and malfunctioning in employee physiology. Thus, physiological systems which evolved for life in hunter-gather times can be maladaptive in modern contexts.

An Organising Framework

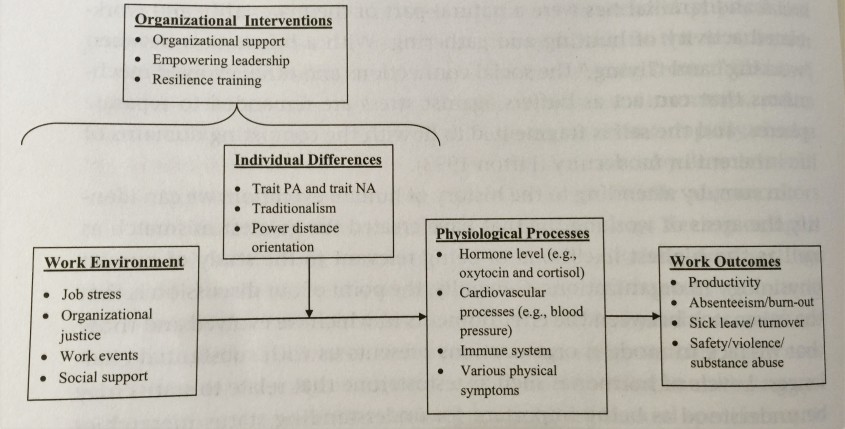

Zhang and Zyphur provide a theoretical framework based on their review of occupational health psychology:

Notice how the authors reconcile traditional constructs within the field organisational psychology, such as organisational support and job stress, with that of physiology. Zhang and Zyphur note that traditional organisational behaviour research focuses mainly on cognitive, affective and behavioural approaches to examine employees’ health and the associated organisational outcomes, and that physiological measures (e.g. elevated blood pressure as an indicator of job strain) have played only a peripheral role.

A key point raised is that measuring physiological functioning is not only important for employees’ well-being, but also for the bottom line. For example, the authors cite a study which found that higher levels of salivary cortisol can explain 25% of the variance in subsequent healthcare costs for organisations. Of course for practising organisational psychologists, one can argue that physiological measures are problematic in regards to cost, time, and data disclosure.

Practical Implications

Within the chapter, Zhang and Zyphur provide some recommendations for promoting a healthy work environment, including job redesign, increasing fairness, and providing adequate support.

The authors believe that job redesign, which addresses the root cause of job stress, can help alleviate the negative impact of high job demands. To ‘increase justice’, Zhang and Zyphur suggest that interpersonal skills should be incorporated into management training. Also, Zhang and Zyphur argue that organisational support and resources should be readily available for employees, including employee assistance programmes and counselling services in the workplace.

One way to contract the adverse impacts of larger status differentials and the impersonal nature of modern organisations on health is to increase the social support employees receive. For example, a study cited found that employees who recieved high social support from their coworkers had lower resting heart rates during and after work. The authors argue that these findings confirm that social support can reduce the mismatch between the modern work environment and that of our ancestors.

For stakeholders in a position to evaluate executive remuneration, appreciate the detrimental impact high income inequality can have on employee health and group functioning.

As stated by Zhang and Zyphur; “More practically, by understanding human evolution and the environments for which we have evolved, it is possible to design interventions to reduce stress by creating a better match between old and modern environments. For example, this could be done at work by creating socially supportive cultures, reducing social and other uncertainties, increasing natural lighting, and minimizing physical space constraints, as well as reducing workloads in employees.” (p. 142).

—

Written by Max Beilby for Darwinian Business

Click here to by a copy of The Biological Foundations of Organizational Behavior

References & Recommended Reading

Boehm, C. (1999). Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior. Harvard University Press.

The Economist (2008) Social Status and Health: Misery Index. Available here

Evans, O., & Steptoe, A. (2001). Social support at work, heart rate, and cortisol: a self-monitoring study. Journal of occupational health psychology,6(4), 361.

Ganster, D. C., Fox, M. L., & Dwyer, D. J. (2001). Explaining employees’ health care costs: a prospective examination of stressful job demands, personal control, and physiological reactivity. Journal of Applied Psychology,86(5), 954.

Marmot, M. G., Stansfeld, S., Patel, C., North, F., Head, J., White, I., … & Smith, G. D. (1991). Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. The Lancet, 337(8754), 1387-1393.

Marmot, M. G., Rose, G., Shipley, M., & Hamilton, P. J. (1978). Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 32(4), 244-249.

Pinker, S. (1997). How the Mind Works. NY: Norton.

Suttie, J. (2016) Why Your Office Needs More Nature, The Greater Good Science Center. Available here

Zhang, Z. & Zyphur, M.J. (2015) Physiological Functioning and Employee Health in Organizations; In Colarelli , S. & Arvery, D. (Eds) The Biological Foundations of Organizational Behavior. Chicago University Press.