Rocked by a steady stream of failed replications and allegations of outrageous fraud, behavioural science stands at a crossroads. Ironically, the field of psychology finds itself slumped in a period of piercing introspection, being forced to answer tough questions.

Diagnoses abound, with blame being placed on perverse incentives in academia, statistical methods in dire need of rigour, and the media’s battle for our eyeballs. But a more fundamental, yet often overlooked, factor is the sturdiness of psychology’s theoretical foundations— or rather, its wobbliness.

Amidst the cloud of this uncertainty, Michael Muthukrishna steps forward with A Theory of Everyone: Who We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We’re Going. In a bold play of the concept ‘a theory of everything’ from the weird world of physics, Muthukrishna, a professor of Economic Psychology at the London School of Economics, ambitiously aims to unify our understanding of human behaviour, culture, and society.

Michael Muthukrishna is a trailblazer in the field of psychology, having recently been recognised as a Rising Star by the Association for Psychological Science, Human Behavior and Evolution Society, and the Society for Personality and Social Psychology. With the precision of an optometrist, Michael brings into focus the intricacies of human uniqueness and the subtle forces of cultural evolution. His scientific work acts as a lens, magnifying our understanding of the evolutionary forces that mould our behaviour and drive cultural change.

Arguably, it was a young Michael being exposed to a rich tapestry of cultures that paved the way for his scientific accolades. Muthukrishna was born in Sri Lanka, and was also raised in Papua New Guinea, Australia, and Botswana. During these formative years, Michael witnessed first-hand the horrors of tribal warfare, including the blood spilled between the Tamils and Sinhalese, and the Sandline Affair, the violent coup of Papua New Guinea. But his childhood wasn’t all drama. Muthukrishna also recalls experiencing awe camping in the depths of in the Kalahari Desert, and the exhilaration of neighbouring South Africa abolishing apartheid. “When you live in so many places, you see how we differ and how we are connected. We swim in different shoals but we are fish in the same body of water.”

While applauding the achievements of popular science books like Yuval Harari’s Sapiens and Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel, Muthukrishna frames A Theory of Everyone as their negative image. Rather than offering ‘The One Thing That Explains Everything’, Muthukrishna reveals a comprehensive framework that can unite a bewildering array of scientific theories, whilst detailing the evolutionary forces that shape all living things on planet Earth.

Just like living creatures, scientific disciplines also pass through key stages of development. Mirroring Newtonian physics, Galileo’s revolutions of astronomy, and Charles Darwin’s discovery of evolution by natural selection, Muthukrishna argues the social sciences are currently undergoing a similar revolution, making the awkward transition from a scrawny teenager to a mature adult.

The human and social sciences are going through puberty. Its curves are showing; its muscles are growing. We are in the midst of a scientific revolution on the scale of Newtonian and Einsteinian physics, the periodic table, and Darwinian evolution. This scientific revolution is a theory of human behavior that, when combined with theories of social evolution, is close to being a theory of everyone.

Which framework does Muthukrishna propose uniting the social sciences under? Dual Inheritance is a theory that outlines how we humans we have two lines of inheritance. No, I’m not referring to the money you’re expecting to inherit from your parents, but rather, the genes and cultural know-how you inherited from them, and the cultural software you’ve downloaded from the world around you.

Since the day bands of archaic humans learnt how to control fire, we’ve inadvertently created a feedback loop where genes and culture continuously shape one another. Sparking fire for cooking is a great example, and explains why we humans have pathetically small teeth and guts, but also abnormally large brains.

Cooking saved us from sitting there like gorillas chewing plants all day or needing four stomachs like a cow munching on grass. We reduced the size of our gut and lost a lot of muscle, saving us a lot of energy. We used that extra energy to fuel a larger brain. What did we do with that larger brain? We learned more useful stuff, including figuring out how to hunt larger, higher EROI [Energy Return on Investment] animals.

At the heart of this theory of everyone, Michael proclaims, is the quest to capture and control energy. All living beings are essentially in a struggle for survival, requiring an energy budget surplus to pay their exorbitant biological bills.

As stated by Michael:

All organisms, including humans, harness the energy around them – from the rays of the sun to the movement of the wind and water – to evolve. Humans have evolved an entirely new way of capturing and controlling energy through cultural evolution. But ultimately energy is at the heart of all that we do and all we can do.

Most of us take for granted the marvels of the modern world. We’re literally surrounded by unfathomably sophisticated technologies that most of us have no idea how they work. It’s as if we’ve been handed inventions created for us by intelligent aliens. But just as fish take for granted the water surrounding them, Michael reminds us how energy-intensive our modern lifestyles are, and how utterly dependent our civilisations currently are on fossil fuels.

As climate science has solidified and the perils of global warming have sharpened into focus, the recent surge in the availability of fossil fuels— thanks to the fracking boom— has muted voices warning of ‘peak oil’. Muthukrishna acknowledges that predictions made by the likes of Thomas Malthus and M. King Hubbert have repeatedly been cast into doubt by the march of technological progress. Yet, he cautions against complacency, pointing out that a technological plateau may loom where no further innovations can make fossil fuel extraction economically viable. “Technology seems to have saved us from the Malthusian trap and delayed Hubbert’s peak oil decline. But those technological advancements have been in the efficiency floor, not the energy ceiling.”

A sceptic could claim that Muthukrishna’s analysis is too reductionist. For example, Muthukrishna circles in on energy scarcity as the biggest threat to large-scale cooperation, and in turn, world peace. Whilst competition over scare resources is one of the main reasons why we fight, wars are messy business that have multiple, tangled causes, where ethnic tensions, balance of power politics, security dilemmas, and the human drives for glory, status and sex all playing leading roles in the outbreak of war. However, I believe Michael is broadly correct in pinpointing energy as one of the ultimate crises of our time. Whilst concerns over the security of our energy sources have been heightened in the Western world following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, so too have concerns about the cost of energy and the sustainability of our fossil-fuelled economies.

Cultural evolution surely encourages us to be humble in our understanding of how the world works. As the biologist Leslie Orgel famously quipped, “evolution is cleverer than you are”. Despite this, Michael proposes bold solutions to address some of the world’s most pressing problems. One of them is championing nuclear power, including pivotal development to make nuclear fusion a commercial reality. The mastery of nuclear fusion would be a major breakthrough for humanity, as it offers the prospect of cheap and inexhaustible energy without poisoning Mother Nature. And contrary to Bane’s brash threats in The Dark Knight, it is impossible to hijack fusion reactors and turn them into bombs. Ultimately, nuclear fusion could well be the technology that saves us from ourselves.

As stated by Muthukrishna:

Once we reach the next fusion-fueled energy level, we will enter a new era of peace and prosperity. It will make our current era, with all its conflicts, seem to our descendants as primitive and barbaric as we see the Middle Ages with its superstitions, witch burning, and horrifyingly brutal wars of conquest.

How can social scientists contribute to such moonshoot missions? Muthukrishna illuminates the way, reminding us that today’s distant planets become tomorrow’s landing sites, powered by the engine of innovation. “Innovation is a social process – a product of a collective brain. Once we realize this, we can become intentional in how we seek information and connect people to maximize the probability of good ideas emerging and spreading.”

This is not mere armchair intellectualising. Muthukrishna has worked with some of the world’s most disruptive companies, sharing his secrets of innovation to enhance their corporate strategies and help solve their thorniest commercial challenges. The cornerstone of these lessons is what Muthukrishna terms the ‘paradox of diversity’.

Much digital ink has been spilled in recent years on the benefits of diversity for promoting innovation, which Muthukrishna’s research backs up. However, it’s also the case that teams who are the least innovative are also the most diverse bunch. How can this be the case? Without a common set of values gluing groups together, Muthkrishna counters, the benefits of diversity crumble.

This seeming paradox of diversity occurs because diversity offers recombinatorial fuel for innovation, but is also, by definition, divisive. Without a common understanding, common goals, and common language, the flow of ideas in social networks is stymied, thus preventing recombination and reducing innovation. But diversity is the most powerful method of becoming more innovative.

Muthukrishna offers sound advice for resolving this paradox, proposing that, like motorists, we must abide by, and respect, a common set of norms to ensure a safe and pleasant journey.

The key to resolving the paradox of diversity is finding common ground on things we don’t share that get in the way of smooth communication. We can overcome these challenges with strategies such as optimal assimilation, translators and bridges, or division into subgroups, which retain diversity without harming communication and coordination.

Muthukrishna does not shy away from dangerous ideas or inconvenient truths. Acknowledging the treacherous terrain he traverses, Muthukrishna ventures into contentious debates on immigration, exploring what these points of friction mean for the fabric of democratic societies. Through these reflections, Muthukrishna stresses the importance of free speech, and the duty of scientists to be open and honest with the public. “Being forthright and truthful about even challenging topics is critical to trust in science. If you can’t trust scientists, you can’t trust science.”

In summary, Michael Muthukrishna’s A Theory of Everyone is more than just a psychology book; it’s a roadmap for understanding and improving our world. It challenges us to look beyond the surface, to rethink our assumptions about human uniqueness, and to embrace the complexities created, and explained, by cultural evolution. A Theory of Everyone is a clarion call for a new kind of understanding – one that may help us solve some of the biggest problems of our time.

Written by Max Beilby for Darwinian Business.

A Theory of Everyone: Who We Are, How We Got Here, and Where We’re Going is published by Basic Books. Click here to buy a copy.

Image credit: The Atlantic.

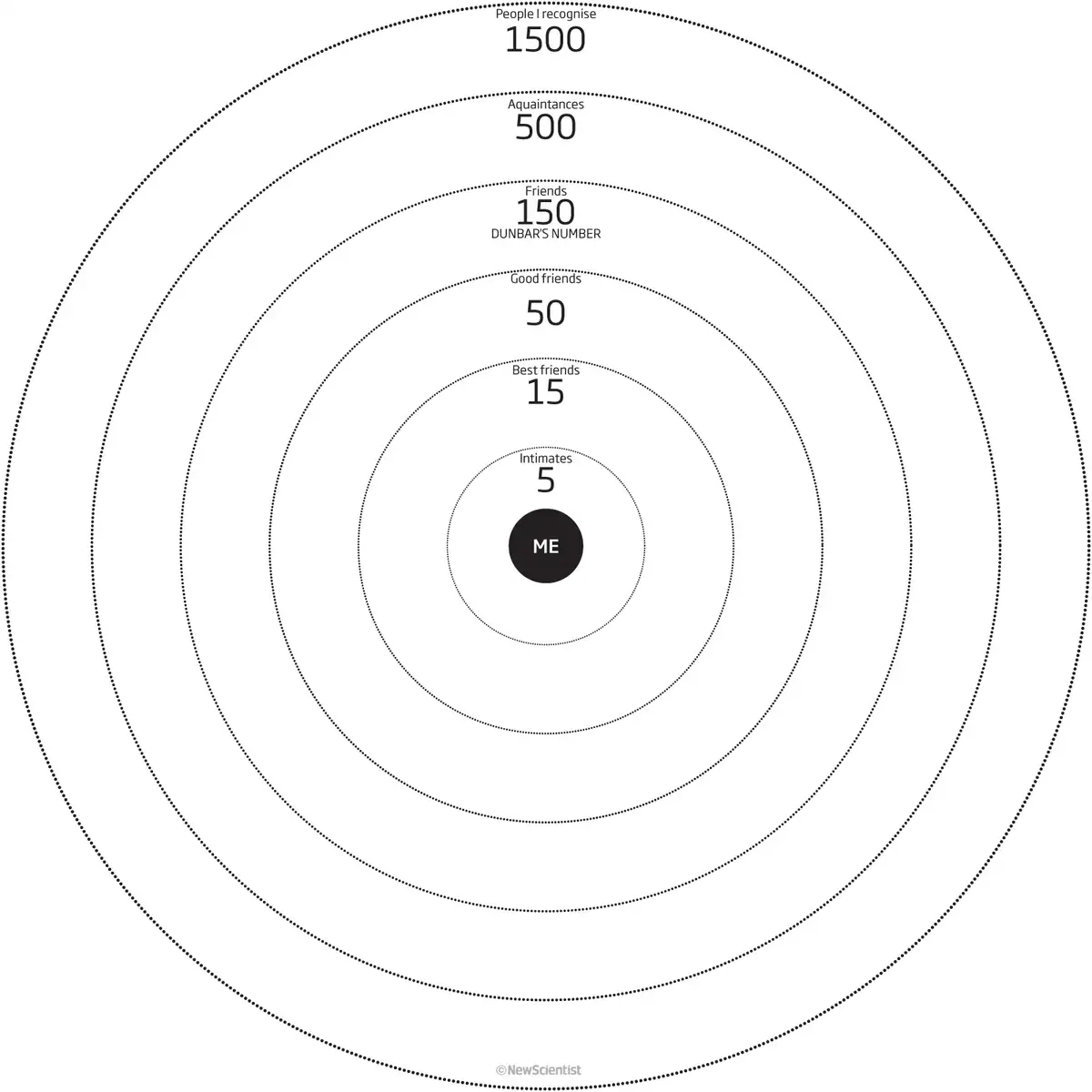

30 years of Dunbar’s scientific research suggests close-knit communities average roughly 150 people. Conversely, each layer of our social networks are roughly 3 times larger than the one inside it, determined by their level of closeness. Image credit: New Scientist

30 years of Dunbar’s scientific research suggests close-knit communities average roughly 150 people. Conversely, each layer of our social networks are roughly 3 times larger than the one inside it, determined by their level of closeness. Image credit: New Scientist