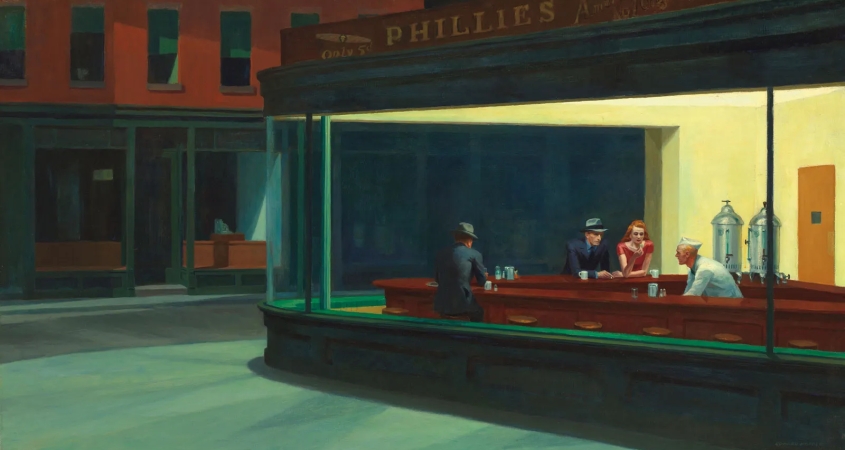

Whether it’s the tragic death of Willy Loman in A Death of A Salesman, or Lester Burnham’s midlife crisis in American Beauty, a persistent theme in popular culture is a gnawing sense of alienation people feel running the modern day rat race.

If you’ve ever felt this way, you’re not alone. Given that we spend the vast majority of our adult lives working, it’s more than understandable why work can monopolise our mental real estate. And whilst work can mould our identities, boost our status and connect us with like-minded people, work by no means makes us immune to loneliness.

What is about working life that can make us feel so alienated and isolated, and what can we do to prevent it?

In The Social Brain: The Psychology of Successful Groups, the legendary psychologist Robin Dunbar joins forces with fellow Oxford University scholars, Tracey Camilleri and Samantha Rockey, where they apply Dunbar’s scientific discoveries to help us work more effectively, and ultimately, more humanely.

Robin spent the better part of two decades studying wild monkeys in Africa, to try and answer the ultimate question: why do some species develop their own societies? Initially, humans were only a fleeting interest to him. However, seeing our common ancestry reflected in our primate cousins forced Dunbar to look inwards.

In another world orbiting Oxford University’s academic universe, Tracey and Samantha were studying another exotic primate: business executives.

Through their executive education at Saïd Business School, Tracey and Samantha heard endlessly of business leaders complaining of feeling disconnected, and at times overwhelmed, by the nature of their work and the sheer size and scale of their businesses’ operations.

Perhaps the size of their groups was a factor, Tracey and Samantha wondered? The authors write:

When we think about teams and groups, we think about their functions and responsibilities and about developing their value to us and the talents of those involved. Only rarely do we stop to think about their size. Can a department be too big to function well? Can a team be the wrong size to cope with the task assigned to it? To what extent can the toxic cultures that sometimes grow up in organisations – the ‘us and them’ mentality – be explained by the size of the groups within them? At what point does a conversation become unmanageable?

To help shed light on these otherwise invisible forces, Tracey and Samantha roped Robin in to teach on their executive programme. Here, Robin gave the corporate bigwigs a rundown on how we humans are constrained by three fundamental factors when navigating our social worlds: the size of the human brain, the release of hormones, and, ultimately, our limited time on planet Earth.

“Many organisations, particularly large ones, ignore the fact that our psychology, as humans, is designed to cope with a very small-scale social world. And, as a consequence, they struggle to function well”, write the Oxford trio. They continue; “By incorporating a better understanding of human nature and its origins, we inevitably have a better chance of playing to its strengths and avoiding the consequences of its weaknesses.”

Named after the big man himself, Dunbar’s Number is the purported natural limit to the number of people with whom we can maintain meaningful relationships with. Informally, Dunbar’s Number is ‘the number of people you would not feel embarrassed about joining uninvited for a drink if you happened to bump into them at a bar’. (Perhaps an updated definition is the number of people you would get scolded for unfollowing on Instagram.)

Having chased down wild monkeys in the heart of Africa, Dunbar discovered a correlation between the size of primates’ brains and their social groups (or, more specifically, the size of their brain’s neocortex, relative to the size of their brains overall. This is thought to be the ‘intelligent‘ part of the brain, which helps us navigate our social worlds). By taking the average size of the human brain’s neocortex and extrapolating the results of other primate species his team had gathered samples on, Dunbar proposed that humans can comfortably maintain around 150 stable relationships.

The first test of Dunbar’s Number was calculating the size of modern hunter-gatherer groups. Why? Because these hunter-gatherer societies reflect the communities humans spent millions of years living in before the advent of agriculture. Coincidently, these hunter-gatherer communities turned out to have an average size of almost 150.

San Bushmen taking a stroll in the Kalahari Desert. The San People have lived in the Kalahari for approximately 20,000 years, making them the oldest inhabitants of Southern Africa. The average size of their bands is estimated to be 152. Image credit: John C. Bruckman

It’s not just brain imaging or yellowing anthropology books where Dunbar’s Number apparently pops up. For example, Dunbar’s team found that the number of people reached by the typical Brits’ Christmas card list was 154. And whilst you might think the infinite reach of social media would allow us to transcend such limits, surveys ran by Dunbar and his team found that the average number of friends Brits had on Facebook was between 155 and 183, which is in the ballpark predicted by the ‘Social Brain Hypothesis’.

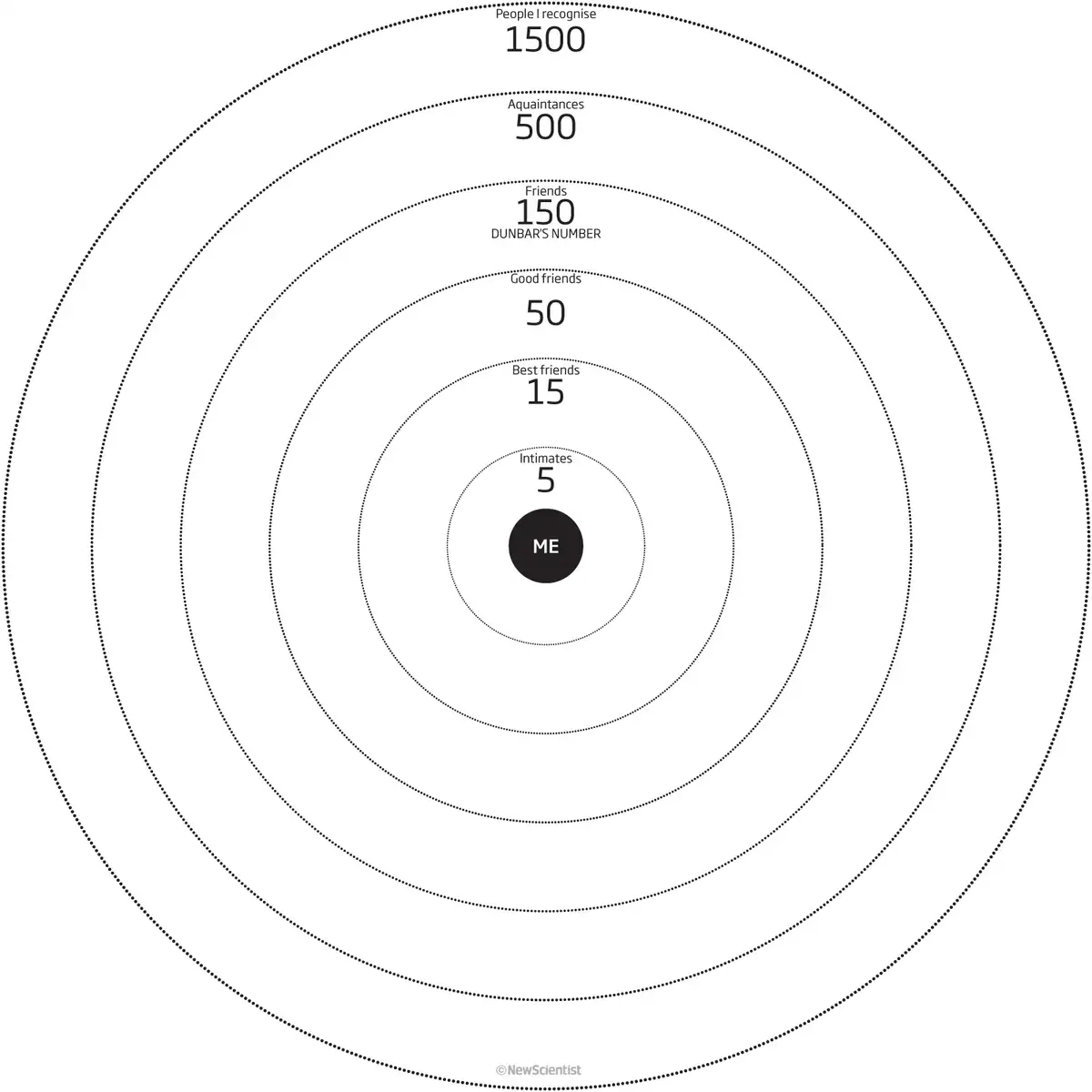

According to Dunbar, our social networks are nested in ‘circles’ or ‘layers’, based on their level of intimacy, following rough powers of three: 5 people to whom we might turn for substantial emotional or financial support in a moment of devastating crisis (say, your romantic partner and close family members); 15 besties who you spend most of your spare time with; 50 good friends (the friends you would invite to your big birthday party), and 150 more casual friendships. Past these shores, you should be able to count up to 500 acquaintances, and you’ll be able to recognise roughly 1,500 people.

30 years of Dunbar’s scientific research suggests close-knit communities average roughly 150 people. Conversely, each layer of our social networks are roughly 3 times larger than the one inside it, determined by their level of closeness. Image credit: New Scientist

30 years of Dunbar’s scientific research suggests close-knit communities average roughly 150 people. Conversely, each layer of our social networks are roughly 3 times larger than the one inside it, determined by their level of closeness. Image credit: New Scientist

Scientists’ best estimate for the age of our species (assuming you’re a modern human) is now 300,000 years old. However, it was not until around 8,000 years ago that archaeologists spot villages of several hundred people cropping up, and not until 5,000 years ago that they count cities totalling tens of thousands of people. “The sea change brought about by living in permanent villages marked a distinct phase shift in the levels of structural stress that people had to cope with.”

Despite our great ancestors lives being far from rosy, Tracey, Samantha and Robin contend that, in humanity’s deep past, the frictions of social life were nixed by living in small, mobile bands. “If the stresses became too much, families were free to leave and find a more congenial group with whom to live. Permanent settlements made this solution impossible.” Once farming opened up Pandora’s Box, new forms of social organisation evolved, including warrior grades, priests, temples, moral codes, and the institution of marriage. “In short, we have been exposed to the stresses of large organisations only for the last few thousand years.”

So, what does this all mean? The main implication of Dunbar’s Number for the business world is that, if a group remains below 150 people, most matters can be dealt with on a largely informal basis. Once you pass 150 or so people, however, dark forces emerge that can destabilise groups. “It becomes more difficult to negotiate arrangements, information doesn’t flow well round the community, processes don’t work quite the way they were intended, silos build up that don’t communicate with each other, people start to be suspicious and less trusting of each other. Some kind of more formal management system becomes necessary to control relationships and transactions.”

Some titans of business seem to have intuitively grasped Dunbar’s Number. Most famously, Bill Gore, the founder of Gore, struggled when he shuffled his workers into their first factory.

One morning, when entering Gore’s newly minted plant, Bill became disoriented when he realised that he did not recognise a single person. In the 1980s, Bill Gore observed that, “when an organisation exceeds some limit, typically 150, people start thinking in terms of ‘they’ rather than ‘we’”. Factory workers couldn’t keep track of each other, and the sense of community Bill had worked so hard to build had gone. With this, Gore made the decision to cap his factories to a maximum of 150 employees. In these smaller factories, Dunbar shares, “everybody knew who was who. Who was the manager, who was the accountant, who made the sandwiches for lunch.”

Wilbert L. (‘Bill’) and Genevieve (‘Vieve’) Gore launch W. L. Gore & Associates from the basement of their home in Newark, Delaware. 1st January, 1958. Image credit: Gore

It’s fair to say that Bill Gore was a maverick. Tracey, Samantha and Robin reflect on the dearth of leader’s heeding Gore’s lessons:

Unfortunately, far too many organisations – from businesses to schools to hospitals and government departments – have ignored the Gore lesson: Scale poses major challenges. As organisations succeed, they grow; in consequence, they inevitably develop fracture lines and inefficiencies that are a corollary of our limited abilities as humans to monitor and manage large numbers of relationships. As a result, many forever teeter on the edge of structural collapse, with a left hand that has no idea what the right hand is doing.

Interestingly, the Oxford trio concede that Gore’s policy of ‘150’ is not actually a fixed number. Debra France, the former head of learning and development at Gore, is quoted saying; “While our plants were originally set up as small units of 150, they’re now more like 250 – but probably with three shifts a day, so in reality the human unit is still small.”

Although not explicitly mentioned by the authors, debates are taking place in academic circles about the veracity of Dunbar’s Number. Remember Dunbar’s original study, exploring the correlation between primates’ brains and the size of their groups? Biologists stationed at Stockholm University recently tried to replicate Dunbar’s original correlations, using a larger dataset and more up-to-date statistical methods. Their analysis produced wildly different numbers depending on the statistical technique they used, and the uncertainty surrounding their estimates was “enormous”.

Other researchers have argued that the size of primates’ brains is best explained not by their social lives, but rather, what they eat. As fruit is harder to come by than abundant leaves (and therefore requires greater intelligence to obtain), the reasoning goes, having a bigger brain actually helps keep fruit chomper’s hunger at bay.

Despite these criticisms, there is clearly a limit to the number of relationships the human mind can manage. This varies considerably, presumably, by individuals’ intellectual horsepower and the complexity of their cultures, but a limit exists. And whilst brain imaging studies may be a little fuzzy, Dunbar and his collaborators have tried to measure the size of this ceiling using a range of different tools at their disposal.

Admittedly, calls to cleave a new business unit once the 150 mark has been breached is a tough sell. However, Tracey, Samantha and Robin also provide helpful guidance on forming teams that can be immediately implemented. Generally, work teams can comfortably range from 6 to 12 people, assuming everyone has a crystal clear understanding of their role. However, if chaos strikes and you need to make quick decisions during a moment of crisis, a team of 5 firefighters is most appropriate. Conversely, 50 is a good number for an expansive knowledge sharing session, so long as you have a attendant chair with a meeting agenda.

Whilst Dunbar’s Number gets a starring role in The Social Brain, it is not the only story. Having interviewed 50 eminent business leaders for their book, Tracey, Samantha and Robin share invaluable insights on how to help people survive and thrive in the wilderness of large corporations.

The wisdom distilled in The Social Brain boils down to one truism: organisations are not machines. Rather, organisations are collections of humans that possess a range of social superpowers, but also, mental limitations. “Management practices that have dominated thinking for the last century or so have invariably imagined organisations as akin to a clockwork mechanism. Improving the efficiency of an organisation is simply a matter of pressing the right buttons.”

Although industrialists of the 19th century made profound breakthroughs in increasing efficiency and scale by mechanistically dissecting management practices, the Oxford trio argue that the long shadow of the machine metaphor is now limiting human progress. “It’s not just that the machine metaphor is incorrect, either. It’s also harmful. In its construction of a world of predictable, robotic performance, it creates an assumption that, if human efforts fall short, the problem must lie with the individual concerned, not the system.”

Since the dawn of industrialisation, workers have lamented feeling mechanised, being reduced to mere cogs in a wheel. Today, as we grapple with the rapid evolution of artificial intelligence, our anxieties are rooted in artificial intelligence making us redundant.

Rather than replace us, let’s hope breakthroughs in machine intelligence will help us embrace our humanity.

Written by Max Beilby for Darwinian Business.

The Social Brain: The Psychology of Successful Groups is published by Penguin. Click here to buy a copy.