In 2017, Collins Dictionary crowned ‘fake news’ its word of the year.

Collins’ entry can be credited to two unforgettable events that defined 2016: the decision taken by the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, and the election of Donald J. Trump as President of the United States. Dismayed and disoriented by the outcome of these votes, elites on both sides of the Atlantic were quick to say misleading statistics and outright lies precipitated these political earthquakes.

Like the coronavirus itself, misinformation has also exploded during the pandemic. When COVID began permeating our borders, the head of the World Health Organisation warned that “we’re not just fighting a pandemic; we’re fighting an infodemic”.

This raises the question: how impactful is misinformation generally, and are we really as vulnerable to propaganda as pundits make us out to be? Not quite, argues French cognitive scientist Hugo Mercier in his new book, Not Born Yesterday: The Science of Who We Trust And What We Believe. Rather than being easily duped, Mercier argues that, ironically, we are not as gullible as we’ve been led to believe.

The case against gullibility

For many, Mercier’s argument will seem rather odd. Following the atrocities committed during World War Two, social psychologists have spent the past 70 years detailing the various ways we frail humans are vulnerable to social influence and persuasion. Some of social psychology’s most infamous experiments suggest that we are all natural conformists, forming our beliefs and altering our behaviour in order to fit in with the group and be in our bosses’ good books.

Despite the case for gullibility seeming an easy verdict, Mercier objects, stating that the case is far from settled. Rather than being gullible, Mercier argues, each of us come fully equipped with mental hardware, an ‘open vigilance’ system, that, most of the time, can correctly determine who we can trust, and what is ultimately true.

Viewed through the lens of evolutionary biology, Mercier argues that pure gullibility would be too easily taken advantage of by unscrupulous actors, and thus isn’t an evolutionarily stable strategy. “What should be clear in any cases is that we cannot afford to be gullible”, Mercier writes. “If we were, nothing would stop people from abusing their influence, to the point where we would be better off not paying any attention at all to what others say, leading to the prompt collapse of human communication and cooperation.”

Despite our bullshit detectors working well most of the time, Mercier argues that we’re prone to making mistakes when we’re navigating new environments that evolution hasn’t fully equipped us to deal with. What does this mean? Mercier argues that the prevalence of conspiracy theories and antiscientific beliefs can be explained, at least in part, by how intuitive these ideas are.

Take vaccines for example. Most of us have no clue how vaccines work, and the idea of injecting your healthy child with an alien substance can ring alarm bells. “All our intuitions about pathogens and contagion scream folly.” Despite the remarkable successes of vaccination programmes over the past century, communicating the effectiveness and safety of vaccines clearly remains one of the scientific communities’ thorniest issues. “In the absence of strong countervailing forces”, Mercier writes, “it doesn’t take much persuasion to turn someone into a creationist anti-vax conspiracy theorist.”

Mass persuasion

Mercier documents the astronomical funds paid for Western political campaigns, with the US presidential election taking centre stage. Given the mountains of money ploughed into these political campaigns, you would expect a commensurable return on investment. However, you may be short changed. Mercier argues that the scientific research on whether political campaigns can sway public opinion and win elections has produced surprisingly ambiguous results.

Rather than being able to socially engineer the masses’ political preferences, Mercier argues propagandists can only craft messages that already resonate with the public. “With a bit of work, they will be able to affect the audience at the margin, on issues for which the audience is ambivalent or had weak opinions to start with. Yet many have granted prophets the power to convert whole crowds, propagandists the ability to subvert entire nations, campaigners the skill to direct electoral outcomes, and advertisers the capacity to turn us all into mindless consumerists.”

Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda Minister, is hailed as one of history’s master manipulators. Generally speaking, historians hold mixed views on the potency of Nazi propaganda. Provocatively, Mercier proclaims that essentially no persuasion took place in Nazi Germany. Rather, Mercier suggests that Hitler and his henchmen road on a ticket to heal the humiliations that Germany endured in the aftermath of World War One.

As stated by Mercier:

The power of demagogues to influence the masses has been widely exaggerated. . . If one steps back for a moment it soon becomes clear that what matters is the audience’s state of mind and material conditions, not the prophets’ power of persuasion. Once people are ready for extreme actions, some prophet will rise and provide the spark that lights the fire.

If propaganda is so staggeringly ineffective, why do millions of people living under authoritarian regimes act like they’ve been brainwashed? The answer, according to Mercier, is simple. Authoritarian regimes that plaster billboards with propaganda also closely surveil their citizens, and crush any whiff of dissent. Given their plight, it is entirely understandable why people living under repressive regimes would want to keep their mouths shut, out of fear for their personal and family’s safety.

Mercier hammers the point home:

Failure to perform the Nazi salute was perceived as a symbol of ‘political nonconformism’, a potential death sentence. In North Korea, any sign of discontent can send one’s entire family to prison camps. Under such threats, we cannot expect people to express their true feelings. Describing his life during the Cultural Revolution, a Chinese doctor remembers how “to survive in China you must reveal nothing to others”. Similarly, a North Korean coal miner acknowledged, “I know that this regime is to blame for our situation. My neighbour knows our regime is to blame. But we’re not stupid enough to talk about it.”

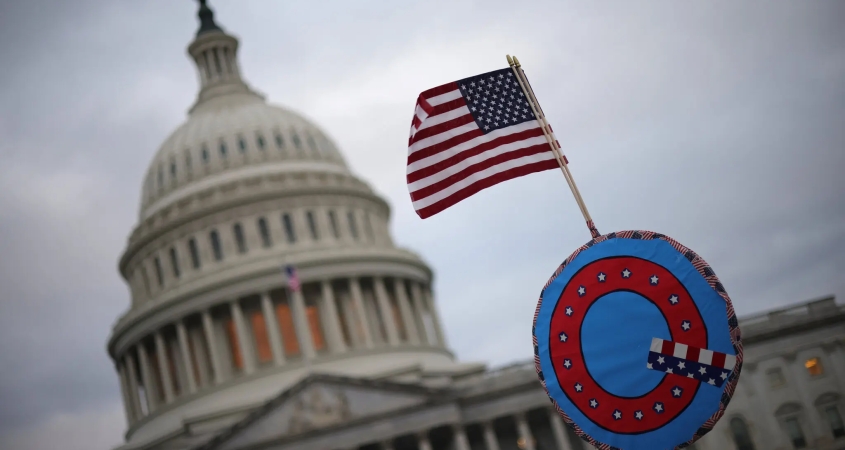

If repression explains acquiescence in authoritarian regimes, why do seas of people in freer societies also act like they’ve been indoctrinated? According to Mercier, professing bizarre beliefs isn’t necessarily a symptom of gullibility. Rather, jarring public declarations can serve as an oath of loyalty.

Take overinflated compliments. Mercier argues that domineering leaders don’t fish for compliments because they actually believe the lavish praise heaped onto them. Rather, excessive flattery can serve as a reliable signal of commitment to his or her reign. Counterintuitively, the more over the top and outrageous the flattery is, the more effective it can be. Why? Because the orator is demonstrating a willingness not only to burn serious social capital, but also to burn bridges with other groups they may be members of— thereby credibly signalling their allegiance to the cause.

It’s hard to believe that people would boldly pronounce absurd or repugnant views for these reasons, but loudly broadcasting outlandish views is precisely what is required to pledge one’s loyalty (say, that Hillary Clinton ran a child-sex ring out of a local pizzeria). With this, Mercier argues we shouldn’t always assume that people actually hold the batshit beliefs they regurgitate.

“People aren’t stupid”, Mercier writes. “As a rule, they avoid making self-incriminating statements for no reason. These statements serve a purpose, be it to redeem oneself or, on the contrary, to antagonise as many people as possible. By considering the functions of self-incriminating statements, we can react to them more appropriately.”

Psychological operations

With growing alarmism over the proliferation of misinformation, Mercier’s sceptical inquiry into credulity is both refreshing and somewhat reassuring. Rather than misinformation causing people to believe absurd things, Mercier argues that this account gets causality backwards. Internet trolls are not so much persuaded by misinformation, but rather, they consume and share it to attack and infuriate their political foes.

Although Mercier makes a strong case for the limited role gullibility plays in our digestion of information, I still have my doubts. Take disinformation pumped out by the Kremlin. Written before Putin launched his ‘special military operation’, Mercier claims that Russian propaganda in Ukraine succeeds modestly when preaching to the choir, and backfires when targeting Russia’s opponents. However, I suspect the Kremlin’s firehose of falsehoods has been more impactful than this.

Whilst it’s unlikely that the majority of Russians buy Putin’s torrent of lies, the core narrative that Western nations are the real aggressors in this war clearly holds sway in Russia. Mercier stresses that public opinion research conducted in autocratic regimes cannot be trusted (if you might be thrown in jail or murdered for criticising your government, I’m sure you’d also keep schtum). However, clever experiments allow people to indirectly express their true preferences. A month after Russian tanks began rolling into Ukraine, researchers using these innovative methods found widespread support for the invasion amongst Russians.

Perhaps there’s another layer of this onion that we need to peel. In his new book The Story Paradox, Jonathan Gottschall argues that it is stories that hold the main sway over our hearts and minds, rather than postulates of factual information. Whilst stories help bind groups of people together, Gottschall reveals the dark side of storytelling, warning that stories can fuel hostilities and tear societies apart. In contrast to factual claims, stories are a potent form of persuasion that pack lots of baggage into little packages, and therefore cannot be easily evaluated through fact checking.

One could argue that Mercier underestimates the dangers of modern information warfare. But of course, any attempt at questioning the veracity of open vigilance would make Mercier proud. If you try to argue against open vigilance, you lose the battle the moment you show up.

Rebuilding trust

Stepping back, what should we do with this knowledge? Before gossiping with a friend or hitting retweet, Mercier encourages us to ask ourselves what the practical consequences of sharing these rumours are, and whether the actions that follow would land us in hot water. By anticipating the consequences of our actions, we are less likely to be part of the problem. To be part of the solution, Mercier says we should penalise those who spread false rumours, or at the very least, deny them kudos for doing so.

Whilst social media giants have been getting a good bashing from politicians on both sides of the aisle, Mercier and his colleagues’ research suggests that, when it comes to the dissemination of misinformation, social media is not the problem per se. False rumours have been told since the dawn of human language, and there are arguably greater societal forces crashing over us that are powering political polarisation within Western democracies.

The take-home message of Not Born Yesterday is that, contrary to what many TED Talk gurus will tell you, influencing people is incredibly difficult. Far from being too trusting, Mercier argues that, generally speaking, we don’t trust enough. In other words, we tend to hold our guards up, where we’d benefit from lowering our defences more often than not. With this, Mercier encourages us to give the man in the street the benefit of a doubt, and to be more trusting of experts.

Of course, it takes two to tango. For experts’ opinions to carry weight, trust needs to be nurtured and sustained. To curb the spread of conspiracy theories, Mercier suggests the best strategy isn’t employing an army of fact-checkers, but rather, rebuilding trust in our key institutions (say, by passing strong laws against corruption). Trust is the glue that binds society together, and as the cliche goes, building a solid house starts with a strong foundation.

Written by Max Beilby for Darwinian Business.

Not Born Yesterday: The Science of Who We Trust And What We Believe is published by Princeton University Press. Click here to buy a copy.