As workers across the corporate world have begun scuttering back into their offices, many of us are sneaking away with our comrades for a drink. Given the substantial hazards alcohol presents, what should our stance on drinking with our colleagues be?

In his new book Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilisation, Edward Slingerland, a Professor of Philosophy at the University of British Columbia, leaps to the defence of alcohol, arguing that the benefits of drinking have essentially been disregarded by public health experts and policy wonks.

Alcohol is evidently a lethal drug. The World Health Organisation blames alcohol for 3 million deaths every year. Not only does alcohol trash our health and strain our healthcare systems, alcohol-fuelled crime wreaks havoc in our communities and drains public finances. And behind the cold statistics of deaths and government spending, alcohol addiction has ruined many people’s lives and caused immense suffering within families.

Defending drinking may appear crass to people concerned about harms inflicted by alcohol, including those of us who have suffered first-hand from the ills of alcoholism. However, Slingerland argues that only by stepping back and seeing drinking through the lens of evolution can we have a proper debate about the costs and benefits of drinking.

To date, scientists’ main explanation for our thirst for firewater has been either ‘hijack’ or ‘hangover’. The white jackets in the hijack camp claim alcohol parasitises our brains’ reward systems, whereas those endorsing the hangover theory see drinking as an ‘evolutionary mismatch’. That is, getting a little tipsy may have been beneficial for our distant ancestors. But in the modern world awash with cheap booze and happy hours, drinking has become deleterious.

Although plausible, Slingerland pours cold water (or rather, warm beer) on these explanations. “Evolution isn’t stupid”, Slingerland quips, where he argues that evolution can happen much faster than most people think. “If ethanol happens to pick our neurological pleasure lock, evolution should call in the locksmith. If our taste for drink is an evolutionary hangover, evolution should have long ago stocked up on the aspirin. It hasn’t”.

Like an expert mixologist, Slingerland melds evidence from disparate fields including archaeology, history, neuroscience and social psychology. Far from being an evolutionary mistake, Slingerland argues that chemical intoxication has helped humans overcome an array of social challenges. For example, drinking helps alleviate stress and anxiety, especially in awkward social situations. Similarly, Slingerland claims hitting the bottle helps build trust and cohesion amongst strangers, providing a quick and easy way to get ‘fiercely tribal primates’ to cooperate.

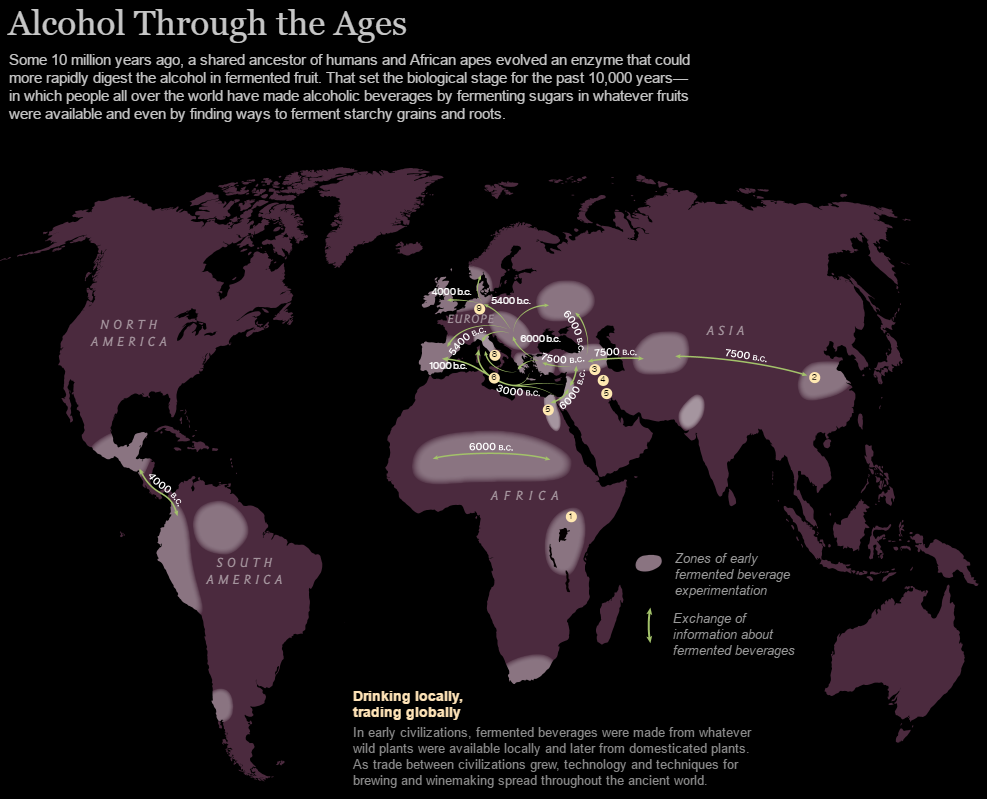

“Humans have been getting drunk for a really long time”, Slingerland writes. He points to this, along with the ubiquity of drinking across cultures, as the primary evidence for alcohol’s adaptiveness. “Images of imbibing and partying dominate the early archaeological record as much as they do twenty-first-century Instagram.”

Of course, religions such as Islam have come down hard on alcohol like a ton of bricks. Although Slingerland concedes that “in the cultural evolution game, Islam has been extremely successful”, he questions how strictly curbs on alcohol have actually been enforced in the Muslim world. Slingerland also emphasises the efforts to outright ban alcohol, whether in ancient China or more recently in the United States, have all essentially failed. “If a ban on alcohol were a cultural evolutionary killer app, you’d expect it to be more consistently enforced”.

Incredibly, Slingerland goes as far to argue that alcohol consumption played a starring role in the rise of large-scale human civilisations (known as the ‘beer before bread’ hypothesis). In support of this theory, archaeologists working in the Fertile Crescent have been surprised by their findings: the tools and grains they’ve unearthed seem more suited to brewing beer than for making bread. Slingerland argues the best explanation is that these hunter-gatherers were stocking up on the magic sauce for an epic religious experience. Although the jury is still out, this proposition challenges existing narratives about how agriculture got the ball of human civilisation rolling.

Although other drugs also play a role in this story, Slingerland crowns alcohol as the ‘unchallenged king of intoxicants’. Whatever the benefits of other recreational drugs are, Slingerland claims none of these potions offer alcohol’s full suite of features.

As stated by Slingerland:

It’s challenging to negotiate a treaty whilst high on mushrooms; the cognitive effects of cannabis show a high degree of variability between people; And dancing all night without food or sleep makes it really hard to show up for work in the morning. A two-cocktail hangover is, in contrast, a relatively minor burden to bear. This is why alcohol tends to displace other intoxicants when introduced into a new cultural environment, and has gradually become ‘the world’s most popular drug’.

That alcohol serves as a social lubricant may not be an earth-shattering revelation. Another less obvious benefit of drinking is that it gets our creative juices flowing. Slingerland endorses the ancient trope that poetic inspiration can be found at the bottom of a bottle. Indeed, Slingerland’s idea to write Drunk was seeded whilst boozing with Google employees.

When it comes to communal bonding and creativity, Slingerland singles out the prefrontal cortex as the enemy. The prefrontal cortex is the most evolutionary novel part of the human brain, and is the motherboard of rational thinking. Slingerland says the prefrontal cortex is arguably what makes us human, but that it also trips us up.

To embody the tension between self-control and creativity, Slingerland draws on Greek mythology. Apollo, the son of God, symbolises rationality, order, and self-control. Conversely, Dionysus is the God of wine, drunkenness, chaos, and fertility. So, what’s the moral of the story? If we want to be more creative, we need to quieten our overly controlling prefrontal cortices. Slingerland argues that alcohol is perfectly adapted to mute the prefrontal cortex, giving us permission to be more open and present in the moment. In other words, allowing our inner child to reemerge.

Being human requires a careful balancing act between Apollo and Dionysus. We need to be able to tie our shoes, but also be occasionally distracted by the beautiful or interesting or new in our lives. Apollo, the sober grown up, can’t be in charge all of the time. Dionysus, like a hapless toddler, may have trouble getting his shoes on, but he sometimes manages to stumble on novel solutions that Apollo would never see. Intoxication technologies, alcohol paramount among them, have historically been one way we have managed to leave the door open for Dionysus.

In summary, Drunk is both fascinating and hilariously fun. Exploring alcohol consumption through the lens of cultural evolution provides nuance and perspective on drinking that has so far been lacking. Combined with Slingerland’s sharp wit and exquisite writing, Drunk packs a punch.

As is always the case, there are quibbles one could raise. I’m sure sceptics will contest the adaptationist programme that Slingerland subscribes to. To elaborate, Slingerland points to the prevalence of drinking across cultures and throughout history as the primary evidence for alcohol being a cultural adaptation. However, could this reasoning not also be used to argue that trephining and bloodletting were ‘adaptive’ too? Understandably, scientific studies that directly measure the effects of alcohol on groups’ performance are sparse. More research in this space would presumably bolster Slingerland’s claims of alcohol’s benefits.

Slingerland mentions ‘Asian flushing’, where some people with Asian ancestry experience unpleasant side-effects when drinking. Possessing the gene responsible for alcohol flushing, ‘ADH1B’, dramatically lowers your odds of abusing alcohol. ADH1B has been kicking around the gene pool for at least 7,000 years, where Slingerland argues it should spread like wildfire if drinking was merely an evolutionary mistake. However, what’s interesting is that this gene is most common in areas of Asia where some of the earliest cases of drinking have been documented. So if Asia got the party started, perhaps evolution’s locksmiths are already on their way?

Ironically, Slingerland comes full circle and presents a revised version of the ‘hangover’ theory. The arrival of spirits dramatically raised the stakes of drinking, allowing anyone to consume a lethal amount of ethanol in just a few gulps. “It is very difficult to pass out from drinking beer or wine; it is nearly impossible to kill oneself,” Slingerland writes. “Once distilled liquors are in the mix, however, all bets are off.” Infused with the modern epidemic of loneliness and binge drinking cultures in the Northern hemisphere, Slingerland argues that spirits may fundamentally change alcohol’s balance sheet, moving alcohol from being a net-benefit to a net-harm.

Drunk is filled to the brim with references to the workplace. According to Slingerland, appreciating alcohol’s ancient roots can help us think more clearly about what role drinking should play in our professional lives.

Slingerland penned Drunk during the coronavirus pandemic, where he says it will take us years to fully understand how lockdowns and home working have impacted innovation. Slingerland observes that the length and scope of our conversations through Zoom have narrowed, where our discussions have become more regimented. “Video meetings are probably more efficient; But efficiency, the central value of Apollo, is the enemy of disruptive innovation.”

Parallel to the challenge of hybrid working is prioritising business travel in a post-pandemic world. According to Slingerland, the ultimate function of business travel mirrors our thirst for firewater. “Neither makes sense unless we discern the cooperation problems to which they are a response.” Whilst most of us are happy buying goods online from a faceless website, Slingerland says he’d hesitate to enter into a foreign business venture if he didn’t know who he was getting into bed with. “If I am entering into a long-term, complex venture with a company in Shanghai, where the impact of screwups or corner-cutting or backstabbing or simple fraud is multiplied a thousandfold, I need to know that the people I’m dealing with are fundamentally trustworthy.”

By coincidence, a key requisite for doing business in various countries is the drunken banquet. “In the modern world, with all of the remote communication technologies at our disposal, it should genuinely surprise us how often we need a good, old-fashioned, in-person drinking session before we feel comfortable about signing our name on the dotted line.” For Slingerland, folk wisdom that we’re more honest whilst drunk rings true. With our prefrontal cortex compromised, aspects of our personalities that we successfully suppress will inevitably burst to the fore. “You may seem like a nice person on the phone, but before I really trust that judgement I would be well advised to reevaluate you, in person, after a second glass of Chablis.”

Whilst toasting to rituals like the drunken banquet, Slingerland doesn’t gloss over the worse aspects of drinking. For example, Slingerland warns of drinking cliques reinforcing the ‘old boy’s club’. Here, he reflects on his own university department’s pub sessions, where those who attended were virtually all men. “Female colleagues were welcome, indeed encouraged, to join, and occasionally did. But it was usually about as male-dominated as the Japanese water trade.” Although problematic, Slingerland argues the solution is not immediately obvious. “Given the demonstrable payoffs of this sort of alcohol-lubricated brainstorming, it seems counterproductive to declare that it should never happen. And yet there are obvious dangers of exclusion and inequity”.

Ultimately, Drunk is a love letter to the Greek god Dionysus. However, your Apollonian inner parent may ask if Dionysus is a lover you should really be courting.

Written by Max Beilby for Darwinian Business.

Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilisation is published by Little Brown Spark. Click here to buy a copy.