Do you ever get a niggling feeling that other people are doing better than you? Don’t worry, we all do.

In his new book The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It, Will Storr reveals the hidden force that triggers much of our anxiety: social status. From our hunter-gatherer ancestors who roamed the African Savannah, to the office workers and internet communities of the 21st century, Storr argues that the human need for status is ancient, universal, and remains deeply ingrained in all of us.

Will Storr is an award-winning journalist and author, who also runs a successful writing course based on his last book, The Science of Storytelling. That Storr has now turned his attention to the psychology of status may initially raise some eyebrows. Storr clarifies that while The Science of Storytelling thrusts our ‘self-serving inner-hero’ into the spotlight, The Status Game reveals the status seeking ‘mechanism’ that lurks behind the scenes. “If the conscious experience is organised as a story, this book concerns the subconscious truth that lies beneath it”

In The Status Game, Storr clarifies that status seeking isn’t a frivolous activity: it’s intricately intertwined with our ultimate evolutionary goals. For all social creatures on planet Earth, high status brings abundance: finer food, more land, and more romantic opportunities (for men at least). “The higher we rise, the more likely we are to live, love and procreate. It’s the essence of human thriving. It’s the status game.”

The psychological toll of being at the bottom may be obvious. Less intuitive is how our rung on the social ladder affects our bodies. Like monkeys sitting atop their troop’s dominance hierarchy, high status men and women are generally healthier and live longer than their underlyings (although male baboons show that life at the top can be tough too). Painstaking studies conducted with British civil servants suggest this has less to do with the privileges that comes with affluence, but rather our relative rank. “To our brains, status is a resource as real as oxygen or water”, Storr writes. “When we lost it, we break.”

Success, virtue and dominance

In The Status Game, Storr reveals the doubled-edged nature of human status seeking, documenting how striving fuels the best and worst aspects of humanity. Whilst scientists and inventors wanting to make a name for themselves drives human progress, people’s desire to get ahead of the competition also results in murder, war, and even genocide. How do we make sense of status seeking’s mixed scorecard?

Unlike any other animal, we are fully fledged cultural species. We need to be socialised from the moment that we’re born, and we rely on collective wisdom for our survival (how long could you survive on your own in the wilderness?). As a result, we grant people with the expertise our group needs to succeed with high status—a path to success aptly called prestige.

Success and virtue games help explain the psychology of prestige. In success games, status is awarded for exceptional achievements that demonstrate skill and talent in established contests (think of professional sports and tech start-ups). In virtue games, status is awarded to people who are conspicuously moralistic, obedient, and dutiful (think of religious or royal institutions).

Although prototypical forms of prestige have been identified in wildlife, such as elder elephants leading their herds to water, no other species has stretched the psychology of prestige as far as we humans have. As stated by Storr; “prestige is our most marvellous craving.”

Despite our species’ championing of prestige, we’ve never fully stamped out our primitive urge for dominance. That is, gaining status through intimidation, manipulation, and coercion. This type of leadership is ancient, and traces back millions of years to our primate heritage. In the tree of life, human and chimpanzee lineages split off from their common ancestor approximately 5 to 7 million years ago. With this, both primate species took with them a proclivity for dominance hierarchies, and a psychology hypersensitive to dominance.

As stated by Storr:

Whilst the prestige games of virtue and success have made us gentler and wiser animals, the superior modes of playing haven’t completely overwritten our bestial capacities. As psychologist professor Dan McAdams writes, ‘the human expectation that social status can be seized through brute force and intimidation, that the strongest and the biggest and boldest will lord it over the rank and file, is very old, awesomely intuitive and deeply ingrained. Its younger rival – prestige- was never able to dislodge dominance from the human mind.’

Intriguingly, prestige and dominance both appear to be equally effective ways of gaining status. That is, one can rise to the top either by being virtuous and attaining mastery, or by throwing one’s weight around. The crucial difference is that prestigious leaders have been freely chosen by their followers, whereas domineering players typically force people to respect them.

Playing with fire

Across cultures, manhood is widely seen as something that has to be earned, but can also easily be lost (when was the last time you heard someone be told to ‘woman up’?). Because of the precarious nature of manhood, Storr underscores how young men are particularly prone to violent status contests.

Men have a propensity for physical status contests built into their minds, muscles and bones. They’re overwhelmingly the perpetrators of murder, and comprise most of their victims, with around 90% of global homicides being committed by males, and 70% being their targets. In the majority of cases, killers are unemployed, unmarried, poorly educated and under 30. Their sense of status is fragile. In most places, the leading reasons given for killing are ‘status driven’, writes conflict researcher doctor Mike Martin, ‘the result of altercations over trivial disputes’.

Needless to say, not all young men are violent criminals, and culture plays a big role in regulating aggression. However, Storr zeros in on combination he believes blows the powder keg: having a grandiose personality and experiencing intense feelings of humiliation. What’s the connection? Being humiliated is to have your reputation shattered, where your status plummets publicly and in dramatic fashion. “Humiliation can be seen as the opposite of status, the hell to its heaven.”

In the most serious cases, Storr says we sink so far down the rankings that we’re no longer considered useful players. The only way to recover is to start afresh and rebuild from the ground up. However, there’s another option available for those who are slipping and can’t get themselves up: annihilation.

As the African proverb says, ‘the child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth’. If the game rejects you, you can return in dominance as a vengeful God, using deadly violence to force the game to attend to you in humility.

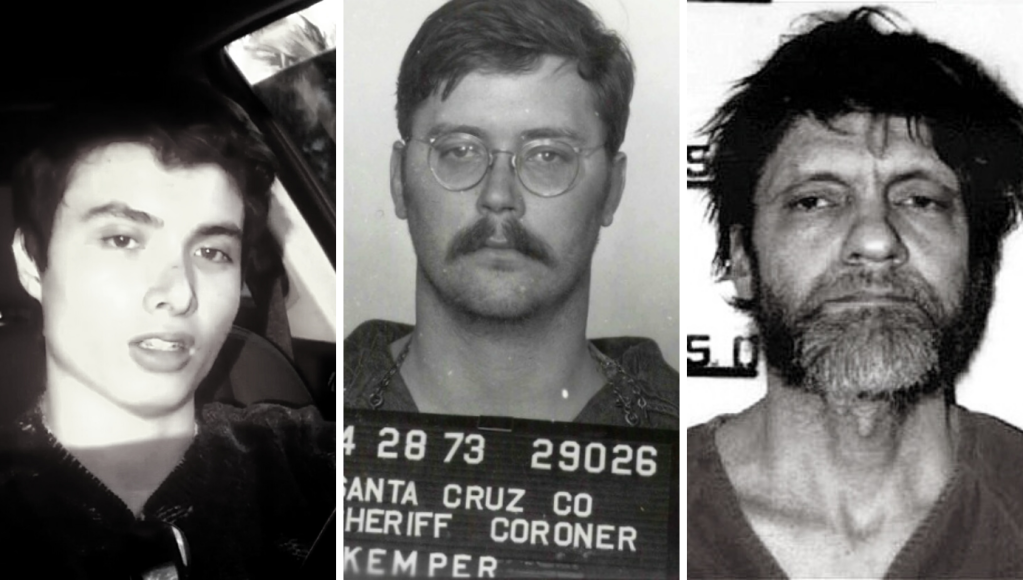

Talk of burning villages down may evoke images of The Joker, but young male ‘incels’ are no laughing matter. Storr provides a harrowing account of three mass murderers: the ‘co-ed’ serial killer Edmund Kemper, who remains one of America’s most notorious murderers; Elliot Rogers, who was responsible for the misogynistic terror attacks in Vista California; and ‘the Unabomber’, Ted Kaczynski. Through his combing of the forensic evidence, Storr reveals how each of these men were not only delusionally narcissistic (Storr avoids making armchair diagnoses and sticks to the term ‘grandiose’ instead), but were also subject to a crushing weight of humiliation.

Of course, several other factors contributed to these men committing such heinous crimes, including the dire state of their mental health. However, Storr argues that mental illness is not a sufficient explanation, as almost everyone who suffers from such conditions are not hellbent on destroying their communities. As stated by Storr:

All three had a need for status that was unusually, perhaps pathologically fierce, and so the humiliations they suffered would’ve been all the more agonising . . . Feeling entitled to a place at the top of the game, they were driven to depravity by life at the bottom.

Learning from history

These powerful undercurrents of grandiosity and humiliation are not confined to dangerous criminals. Storr also spots this sense of entitlement and gnawing resentment in notorious acts of espionage, sabotage, and amongst extreme political movements. Most poignantly, Storr draws parallels with the rise of Nazi Germany.

In attempting to understand the successes of the Nazi Party, Storr implores us to be brave. “The Nazi catastrophe can’t be understood without acknowledgement of why the Germans came to worship their leader as a god”.

Before the outbreak of World War One, Storr claims Germany was the most prosperous nation in Europe (edging ahead of Britain), where Germans’ living standards had been soaring since the turn of the 20th century. When war was declared, the Germans were confident (perhaps overconfident) that this would be a quick victory for the home team.

In the aftermath of Germany’s shocking defeat, Germans expected that the terms of peace would be just. However, the strict provisions that were enforced through The Treaty of Versaille included: 1) accepting blame for starting the war; 2) agreeing to disarm, whilst handing over enormous amounts of military equipment; 3) surrendering vast tracts of land and German territories; and 4) paying today’s equivalent of almost three hundred billion pounds in damages. These terms were almost unanimously felt as a national humiliation.

That Germany had to foot the bill for everyone’s war helped trigger a wave of hyperinflation that was so disastrous, workers had to collect their wages with wheelbarrows. These humiliations multiplied themselves. When Germany inevitably fell behind on its reparation payments, France and Belgium occupied the Ruhr Valley, one of Germany’s major industrial engines. Once hyperinflation had finally been tamed, the Great Depression hit. Germany was plunged into a deeper state of desperation and despair.

According to Storr, Adolf Hitler road on a ticket of healing the humiliations that Germany had endured through the asture terms of the Treaty of Versailles. Although antisemitism was rife at the time, Storr argues Germans’ main priority was restoring what they deemed was Germany’s rightful place at the top.

Partly through effective propaganda, Hitler himself became highly symbolic of the resurgent Germany; By the logic of the status game, he became sacred, the literal equivalent of a God, a figure that symbolised all that his players valued and who, in effect, was their status.

Genocide, Storr argues, is not just about the killing or ‘cleansing’ enemies. “They’re about healing the perpetrators’ wounded grandiosity with grotesque, therapeutic performances of dominance and humiliation.” The Holocaust, the Nazis’ systematic slaughtering of six million Jews across Europe, was scaled up when Germany’s war effort started going south, and continued right up until the end of the Second World War— just as Hitler’s house of cards was crumbling.

The Nazis, Storr proclaims, were just like Edmund Kemper, Elliot Rodger and Ted Kaczynski. “They told a self-serving story that explained their catastrophic lack of status justified its restoration in murderous attack”, Storr writes. “But it’s not just Germany that’s been possessed in this way. Nations the world over become dangerous when humiliated.”

Stepping back, what lessons should we take from The Status Game? By peering into the mind of murderers and murderous regimes, Storr reminds us of the ever present threat posed by tyranny. To make sure we’re not swept away by a visceral rush of dominance, Storr instructs us to continuously question if the groups we belong to are becoming too tight, too dogmatic, and too extreme. For example, Storr states if we’re ever made to feel that acts of violence are virtuous, that’s a red flag. “If we’re serious about ‘never again’ we must accept that tyranny isn’t a ‘left’ or a ‘right’ thing, it’s a human thing. It doesn’t arrive goose-stepping down streets in terrifying ranks, it seduces us with stories.”

Given our peers’ ability to warp our sense of reality, how do we actually know when our groups have become unhinged? The antidote, Storr argues, is to play several status games. In other words, to diversify risk and not put all your eggs in one basket. “People who appear brainwashed have invested too much of their identity in a single game”, Storr states. “If the game fails, or they become expelled, their identify– their very self– can disintegrate. No such risk can befall the player with a diversity of identities who plays diverse games.” Of course, being a member of many groups opens one’s eyes to different views, too.

Conversely, Storr advises us to practice warmth, competence and sincerity when navigating our status hierarchies. “When we’re warm, we imply we’re not going to use dominance; when sincere; we imply we’re going to play fairly; when competent, that we’re going to be valuable to the game itself”.

According to Storr, it’s all too easy to flash sparks of dominance in the heat of the moment, where we draw for force to influence others. However successful this may be initially, Storr stresses that overpowering people, through forms of intimidation or other means, isn’t a sustainable strategy. “The glowers, the sighs, the wails of complaint; such twitches of animalism might help us achieve some immediate goal, but they’ll also lead to our being de-ranked in the mind of others.”

Whilst reflecting on prestige’s sticking power, Storr points out that we all have status to give, and that the credit we can dole out is essentially limitless. “Creating small moments of prestige means always seeking opportunities to use it. Allowing others to feel statusful makes it more likely they’ll accept our influence.”

Like a herd of elephants being led to water, let us continue our miraculous journey and follow the winding path of prestige.

Written by Max Beilby for Darwinian Business.

The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It is published by William Collins. Click here to buy a copy.

*Post updated 11th January 2022